Food traceability refers to having the ability to trace your food item (or even all ingredients in a dish) down to its origin while having transparency on everything happened to it during its journey throughout the supply chain.

Selling sports pharmacology, chemistry, androgen fertility-uk.com and anabolic steroids.

Almost all food supply chains today have some kind of traceability; let it be powered by a cutting-edge digital technology or maintained via simple paper records. However, at the same time, a whistle blows at some corner what do testosterone enanthate in the world literally every week, surfacing a shameful food scandal that has been going on for ages. Naturally the suspicion turns towards the developing world where nation states are highly corrupt and regulatory arms are not strong enough to combat food fraud. However, recent raids by Europol along with many similar events suggest that cheating on food quality is far from rare in the developing world too. How come such a crime exist under day light in such abundance in a legal environment that requires every food supplier to maintain traceability?

Why today’s traceability doesn’t work?

In answering this we need to examine the way traceability is actually practiced in food industry. Stakeholders in food supply chains (producers, processors, transporters, importers, warehouses, distributers, wholesalers, retailers, etc.) maintain traceability of items in their custody because of one or few of the following reasons.

- To obtain compliance so that their products can enter certain markets

- Due to legal requirements

- For internal tracking

- Due to the pressure from a powerful upstream stakeholder (such as a big retail chain asking its suppliers to track certain information)

These are either obligations or internal KPIs than information generated towards the overall betterment of the supply chain. This short-sighted, mediocre intention makes traceability’s value next to zero to the most important stakeholder in the food supply chain: End Consumer.

What do consumers need?

There can be several facets of a food item that a buyer would want to have insights on before consuming it; origin, safety and freshness are some of the obvious. This can extend to more broader aspects such as the community (who are the people I’m supporting by purchasing this product?), fair trade or sustainability (how environment-friendly this product was made?). Lets call them traceability dimensions. Three conditions must be satisfied to assure availability of high quality traceability for the consumer.

- All data necessary to generate the required traceability dimension must have been tracked

- Data tracking should be authentic and accurate

- A decoding mechanism that converts a wealth of tracking data into simple, elegant traceability summary that the consumer can digest

Access to traceability dimensions with high quality will be a driver for certain consumers to pay a significant premium for the food product. Statistics support the fact that a new type of a consumer with knowledge, technical fluency, need and purchasing power to drive such premium markets in massive scale has been emerging during past few decades. However, the real challenge is devising a mechanism which is capable of fairly distributing this potential new wealth generated out of high quality traceability across all stakeholders in a supply chain so that every party involved is motivated enough to play their part right to generate and decode tracking data.

Expectation vs Reality

Economics involved in today’s food supply chains is far from embracing such a value system. There’s almost no incentive for supply chain participants to generate tracking data authentically and pass it along the chain in a way that they ultimately contribute in generating the intended traceability dimensions. Instead they fall into the practice of recording only what is useful internally and is necessary for surpassing regulatory barriers. This has nurtured a culture where hiding and cheating is incentivized, leading to catastrophes in the consumer end.

Traceability is an Organizational Problem with an economic root

To use more sophisticated technology for tracking, storing and presenting traceability data for confronting this dilemma is to get the wrong end of the stick. It is important to recognize the highly organizational nature of the problem. High quality traceability cannot be achieved by the efforts of a single organization regardless of the skill and the tracking technology involved. If at all trustworthy traceability is to become a reality it has to be the result of a collective effort by all participants in a food supply chain. Not to be overlooked is the fact that in a typical food supply chain the participants operate in different geographies and are driven by different economic objectives and value systems. Unless the supply chain is tightly integrated where one organization dictates how others should be doing things, driving every organization in the supply chain towards the generation of high quality, authentic traceability is a serious managerial problem. Even in an integrated supply chain authenticity of traceability data is still in question as the seller’s economic intentions do not necessarily align well with consumer’s.

When the question is of organizational and managerial type, a natural concern arises regarding governance. Who would make sure that the supply chain participants will generate necessary tracking data authentically? Who would ensure authentic interpretation of traceability data so that the consumers get the correct picture? Who would punish the bad guys who try to trick the system for their advantage? Who would be responsible in distributing the new value generated by traceability economy in an acceptably fair scheme among supply chain participants? History has proven that no company, community collective or government cannot be trusted to play this role in their own. Highly lucrative gains in food fraud enable bad players to corrupt any kind of human institution. The case of black caviar is a detailed example for this.

Can Blockchain’s Immutable Ledger provide an answer?

Digital technology has its limitations when capturing the physical world. It has to depend on the competency and authenticity of the people who convert the physical reality into digital record. Food supply chains deal heavily with the physical world, so any digital technology involved suffers from all contingencies this limitation brings in. Therefore to expect the immutable ledger provided by blockchain technology to solve the challenge of authentic food traceability in its entirety is only another uthopia. It’s true that one can achieve ‘Proof of Existence’ of row tracking data by directing them to a blockchain right from their source and thereby assure that they have not been manipulated. However, two big issues still remain:

- Tracking data can be manipulated before being sent to the blockchain

- Consumers can still be misguided by malicious interpretations on raw tracking data

A deeper look into how blockchain technology powers digital money (in fact that’s what blockchain technology was originally created for) ignites new hope towards a holistic approach for traceability beyond the immutable ledger. Bitcoin, the first digital money to be powered by blockchain, deals with the problem of reliably managing the digital record of authentic transactions that took place in the system. In a completely chaotic situation everyone will try to alter the digital record in their favor (doubling their own account balance and so on), ending up in a totally useless digital system which nobody trusts in (well, this is akin to the digital traceability records kept by today’s food supply chains). Bitcoin’s key innovation was to capitalize on the potential value of having a trustworthy record of the flow of digital money to bootstrap and maintain the very mechanism that gives life to this digital record. In bitcoin eco-system, players that contribute to keep the digital record get paid in terms of the value of bitcoin. This ensures inflow of enough record-keepers (because of the incentive) as well as their long term buy-in within the system. Bad guys do not get paid, effectively penalizing them by the value of the resources they have spent.

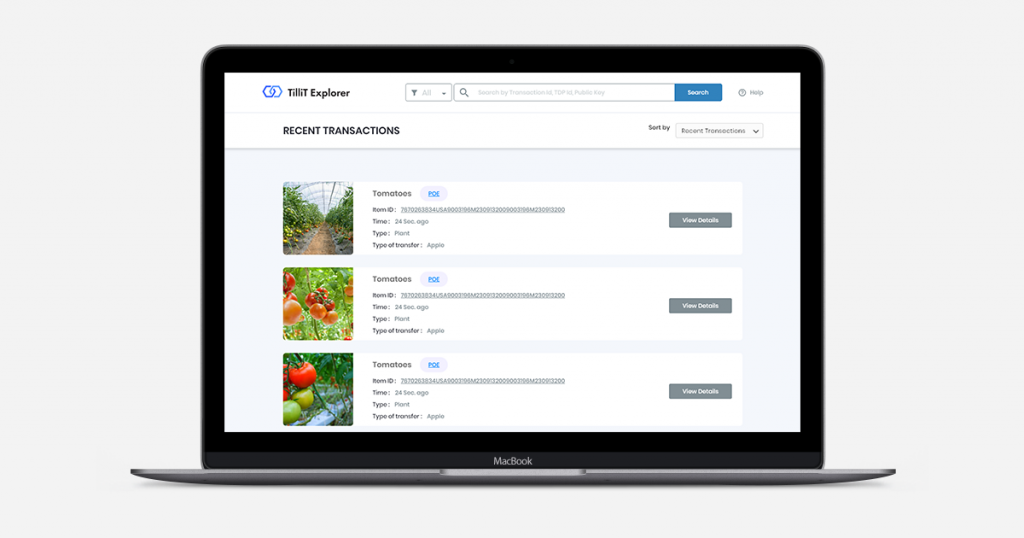

Food traceability involves a multitude of different stakeholders and scenarios compared to digital money, yet it looks plausible to apply the same principles due to the similarities between the two problems in fundamental level. Like in the case of keeping trustworthy record of the flow of digital money, authentic food traceability, if realized, will surely generate a new wealth which is liquid enough to compensate an eco-system of generators and interpreters of authentic, high quality traceability. A blockchain based digital technology that powers such an eco-system will have to provide an acceptable reward / penalty mechanism based on system-judged authenticity level and value of each player’s data in addition to enabling immutability proofs on tracking data, people data and workflows.

About The Author: Admin

More posts by admin