Every time we pick up a product labeled ‘organic,’ ‘sustainably sourced’ or ‘allergen-free,’ we are placing our trust in a promise. That promise, however, rarely begins with the brand on the shelf. It starts much earlier, in a complex web of declarations, certificates and self-attested forms signed by suppliers scattered across the globe. For decades, this system of paper-based trust has been the backbone of the food and beverage industry, a necessary tool for managing sprawling supply chains. Yet, beneath this orderly surface of compliance documents lies a troubling reality: the honor system is often anything but honorable.

The gap between what is declared on paper and what happens in practice is not a minor administrative hiccup; it’s a fundamental vulnerability. It’s the space where horsemeat gets labeled as beef, where conventional grains are sold as organic and where critical safety controls exist only in a filing cabinet, not on the factory floor. This disconnect has profound consequences, eroding consumer confidence, jeopardizing public health and costing companies billions in recalls and lost reputation. The story of modern food safety is, in many ways, the story of learning that a supplier’s word is not enough.

The Illusion of the Checkbox

The reliance on supplier declarations is a product of necessity. As supply chains stretched across continents, physically auditing every farm, mill and processor became impossible. The solution was elegant in its simplicity: ask suppliers to vouch for themselves. This created an ecosystem of certificates for quality management systems like ISO 22000, FSSC 22000 and BRCGS, alongside claims for specific attributes like organic or halal status. On the surface, it creates a tidy paper trail. The problem is that this system is built on a critical assumption: that the economic incentive for honesty always outweighs the incentive for fraud. History has repeatedly proven this assumption false.

High-profile scandals have acted as brutal wake-up calls. The 2013 horsemeat scandal in Europe wasn’t a failure of technology, but a failure of declared truth. Products traveled through a labyrinth of processors and traders, each passing along paperwork that declared the contents as 100% beef. The physical product, however, told a different story entirely. Similarly, the 2008 melamine-tainted infant formula tragedy in China was a catastrophic example of a fraudulent declaration bypassing every safeguard. These aren’t anomalies; they are the extreme symptoms of a systemic condition where the document becomes more important than the reality it is supposed to represent.

How the Paper Trail Frays

The failure of self-attestation isn’t usually a single, dramatic lie. More often, it’s a slow erosion through predictable, recurring cracks in the process. Auditors and risk managers see the same patterns emerge year after year, even in companies with the best intentions.

One of the most common issues is ‘scope creep.’ A supplier might be certified for producing single-origin olive oil, but then begins blending oils from multiple sources, some conventional, some organic, while still using the original certification. The declaration is technically attached to a company name, but no longer reflects the actual product journey. Then there’s the problem of the expired certificate, languishing in a supplier’s file, still presented as current because the renewal audit was too costly or revealed uncomfortable truths.

Perhaps the most insidious failure mode is the weak audit itself. The third-party audit, meant to be the independent validator, can become a predictable ritual. When audits are scheduled months in advance, they can encourage ‘audit-passing behavior’, a temporary state of compliance for the inspector’s visit that doesn’t reflect day-to-day operations. Research has suggested that unannounced inspections often uncover far more critical violations than scheduled private audits. This creates a dangerous illusion of security, where a clean audit report gives a false sense of safety, allowing deeper systemic issues to fester.

The Ripple Effect of Broken Trust

When a supplier’s declaration proves false, the consequences ripple out far beyond a breached contract. The immediate ethical breach is one of consumer deception. People pay premiums for organic food or choose products based on allergen declarations, placing their health and values in the hands of that claim. Fraud undermines that fundamental covenant.

The economic toll is staggering. A single recall can cost tens of millions in direct costs, from logistics and destruction to regulatory fines. The 2013 horsemeat scandal is estimated to have cost the European food industry hundreds of millions of euros. But the deeper cost is reputational. Brand equity, built over decades, can evaporate overnight. Consumer trust, once lost, is agonizingly slow to rebuild. This erosion of confidence has a chilling effect on entire categories, making shoppers skeptical of all claims and punishing honest producers who play by the rules.

On a human level, the stakes are even higher. Undeclared allergens, microbial contamination hidden by falsified test results or adulterants like melamine represent a direct threat to public health. The system’s vulnerability isn’t just a business risk; it’s a societal one.

Beyond the Declaration: Building Real Assurance

The solution is not to drown in more paperwork, but to move beyond paper as the primary source of truth. Leading companies and forward-thinking regulators are shifting from a culture of passive compliance, checking boxes to one of active integrity and verification. This requires a multi-layered defense.

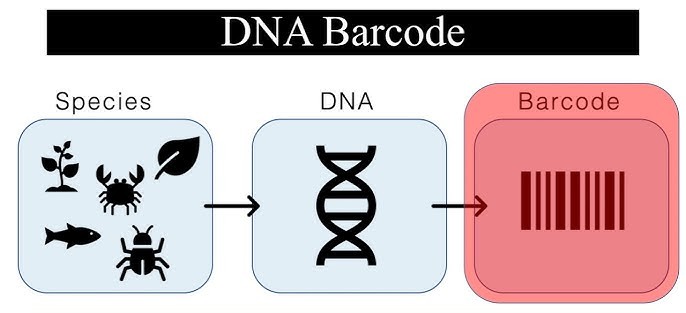

The first layer is enhanced due diligence that treats declarations as a starting point, not an end point. This means validating certificates directly with the issuing body via online databases, conducting unannounced ‘deep-dive’ audits focused on high-risk areas and mandating independent laboratory testing. Technologies like DNA barcoding to verify fish species or stable isotope analysis to confirm geographic origin are moving from niche tools to essential checks for high-risk ingredients.

The second and most transformative layer is digital traceability. While a paper declaration can be forged or misplaced, a digital record on a blockchain or secure platform creates an immutable journey for a product. Imagine scanning a QR code on a package of coffee and seeing not just a country of origin, but the specific cooperative farm, the harvest date and the results of the latest fair-trade audit. This isn’t science fiction; it’s the operational direction of programs like the U.S. FDA’s ‘New Era of Smarter Food Safety.’ This technology shifts the burden of proof from retrospective declaration to real-time, shared evidence.

Finally, there is the human layer: collaboration. The old model was adversarial, buyer versus supplier, auditor versus auditee. The new model recognizes shared risk. Supplier development programs that help smaller producers build robust safety systems, industry-wide platforms for sharing validated data and confidential whistleblower channels create a network of mutual accountability. It transforms the supply chain from a series of handoffs shrouded in information asymmetry into a transparent ecosystem where integrity is the most valuable currency.

Conclusion

The journey of our food from field to fork is one of the most complex logistical feats of the modern world. For too long, we have asked a simple sheet of paper to bear the immense weight of ensuring its safety, authenticity and ethics. That era is ending. The recurring crises and quiet failures have made it clear that trust cannot be self-declared; it must be built, verified and continuously earned. The future of food security lies not in thicker binders of supplier promises, but in the clear light of data, the unannounced visit and the collaborative pursuit of a truth that everyone can see. It’s a future where the promise on the label is guaranteed not by a signature, but by an entire system designed to make lying impossible. That is a promise worth making.

References

- Feed Certification Audit Pitfalls

- Food & Beverage Supply Chains Insights 2025

- Mitigating Supply Chain Risks in Food and Beverage Industry

- The Food Safety Gaps Audits Keep Finding

- Supply Chain Regulatory Compliance Risks

- A Roadmap for Food Fraud Prevention

- Global Economic Crime and Fraud Survey 2022

- Sushi and Seafood Fraud in America

- The horsemeat scandal: what happened, what went wrong, what are the lessons? pdf)

- New Era of Smarter Food Safety Blueprint

- The ISO Survey of Certifications

About The Author: Imandi

More posts by Imandi